IMPACT—Virtual Marine

Nov 19, 2024

By Mathew Channer

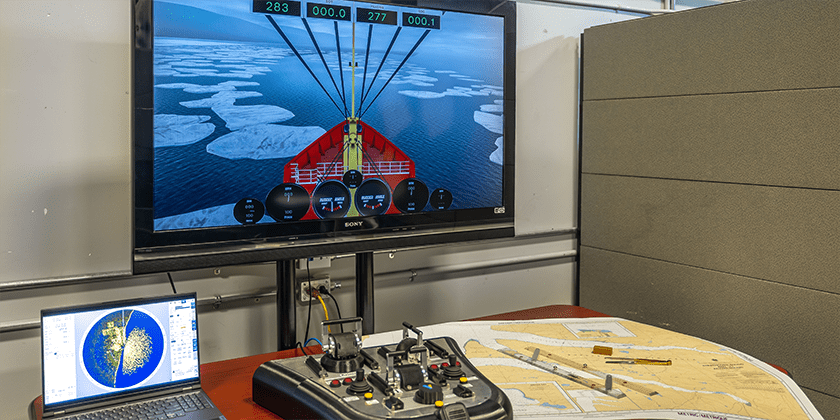

Newfoundland-based company Virtual Marine has spent the last 20 years putting Canada on the map with its cutting-edge development of marine simulator lifeboat training.

Beginning with the oil & gas industry, Virtual Marine set out to revolutionize lifeboat training and save lives around the world. Working in collaboration with the National Research Council, the Marine Institute and Memorial University of Newfoundland, the company formed its headquarters at St Johns, beside some of the roughest seas on the planet.

“We wanted to know, can you teach a person how to launch a lifeboat from an oil rig in a hurricane using a simulator,” said Virtual Marine Managing Director and former Canadian Coast Guard Captain Anthony Patterson.

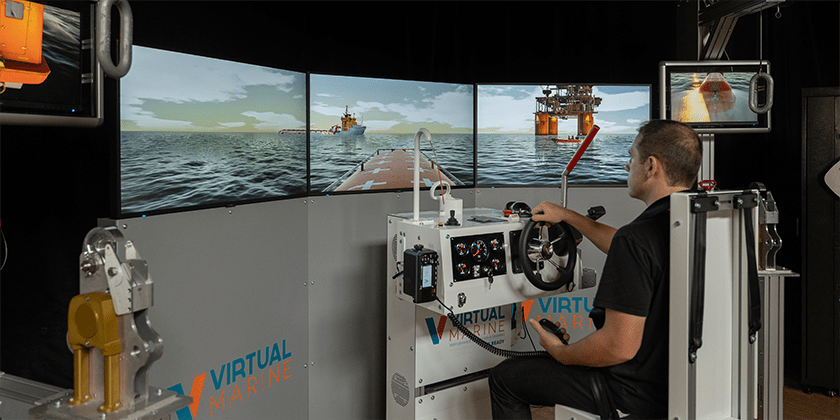

Proving it possible would be more than just a gimmick. At the time, more people in the oil & gas sector had been killed during lifeboat training accidents than lifeboats had saved. Lifeboat launching from large vessels such as cargo ships or oil rigs involves lowering a lifeboat with crew from up to forty feet above the water. Mistakes due to inexperience, even in a training, can be deadly.

“The chance of a death or injury in the practice scenario was more than 70 per cent,” Patterson said. “But with simulators, people can make mistakes, learn from them and move on.”

While the idea was good in theory, Virtual Marine had to overcome stiff industry resistance. Simulation has been used for many years in the marine industry, starting with bridge simulation and then advancing into engine room training. Yet surprisingly, adoption of lifeboat simulation training was slow.

“We spent a lot of time proving that it worked,” Patterson said. “We really invented the technique for simulation augmented emergency drills, and also played a big part in advocating for the change in international regulations for this to happen.”

During early testing, Virtual Marine brought in people who had survived ship sinkings to determine the comparability of the simulator. Without exception, these beta-testers said it was the most real thing they had seen that could match their experience. But the company’s biggest break came in 2020, when global Covid lockdowns forced the marine industry to steer away from traditional hands-on training methods. More people began using simulators and began to see the benefits.

“Our satisfaction ratings are through the roof,” Patterson said. “That’s what drove our company; people started using our simulators and told others it was the best thing they had ever done, and then more people started using it.”

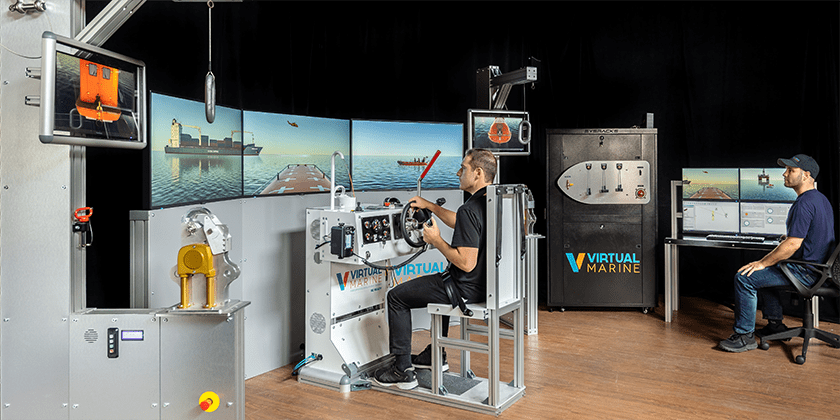

Today, there are nearly 200 Virtual Marine simulators in use around the world, training approximately 8,000 people per year in sectors including oil & gas, shipping, and defense, including the Canadian Coast Guard. Their programs specialize in lifeboat training, fast-rescue craft training, workboat training and ice-breaker training. Patterson says in many cases simulator training is even more effective than traditional methods.

“You can train for things you could never safely do with students in a boat on the water, and you train people to be much more resilient when things go wrong in the real world because they have seen it before in the simulator,” he said.

As well as the significant safety benefits, simulator training allows companies to greatly reduce travel-related expenses and carbon emissions. Training can be conducted anywhere, no longer dependent on coastal facilities.

While Virtual Marine is an internationally established company with simulators all over the world, it has not forgotten it’s Canadian roots. It’s no accident that one of the world’s leading simulator training companies was established in Newfoundland.

“The scientists we have in St John’s are world class,” Patterson said. “And there’s a lot of seafarers here who have worked their entire career in very rough conditions. If you have those experts who can look at the simulator models, they can tune them to make them perfect.”

“When we build our training programs, we build something that we would want to use. Our technologies are optimized for Canada and our operating environment,” he said.

Virtual Marine is very active within Canada and has recently launched a collaboration with Saskatchewan-based first response unit Amphibious Rescue Support Unit One to conduct mobile simulator training for marine first responder units in the prairie regions. The company plans to expand this training to include fire departments, conservation, and other organizations in inland areas.

“That group of people is much wider than the international shipping community,” Patterson said. “We can bring advanced training to people who otherwise wouldn’t have it.”

Virtual Marine’s success has not caused its team to rest on their laurels. They recently began offering simulator training for davit-launched life raft training, marine evacuation systems, mustering procedures, and other vessel evacuation processes. And they are actively working to implement machine-learning into their programs to allow the simulator to interpret the skill level of the user and adjust difficulty settings automatically.

Patterson says he is excited about the future possibilities of marine simulator training, including in the recreational sector, where it has so far been impractical to train aspiring boaters on the water.

“I think where we are going to go is you do your boating knowledge test, and then you get in a simulator,” he said. “You can show you can drive a boat before you get out on the water.”

For more information, visit https://www.virtualmarine.ca/